James Joseph Richardson’s life was forever changed on October 25, 1967, when he and his wife, Annie Mae, returned home from their jobs at a citrus packing plant in Arcadia, Florida, to find their seven children tragically dead. The children—Betty, Alice, Susie, Doreen, Vanessa, Diane, and James Jr.—had been poisoned by parathion, a pesticide, while in the care of a neighbor. The tragic incident, followed by a coerced confession and years of wrongful imprisonment, would become a harrowing story of injustice, ultimately culminating in Richardson’s exoneration and a legacy that continues to advocate for wrongful conviction reforms.

The Tragedy and the Wrongful Arrest

On that fateful day, the Richardson family’s children had eaten a meal prepared by their neighbor, Bessie Reece. Unbeknownst to anyone, the food—grits, beans, rice, and hog jowls—had been laced with parathion, a highly toxic and odorless pesticide. The children, ranging from ages 2 to 8, suffered organ failure after ingesting or absorbing the toxin. By the time help arrived, all seven children were dead.

Bessie Reece, a convicted poisoner from 1951, called James Richardson at noon, reporting that the children were distressed. However, they had already passed away by the time assistance reached them. Despite this, Sheriff Frank Cline targeted James Richardson, arresting him within hours. The investigation and subsequent arrest would set in motion one of the most tragic miscarriages of justice in Florida’s history.

Coerced Confession and Trial

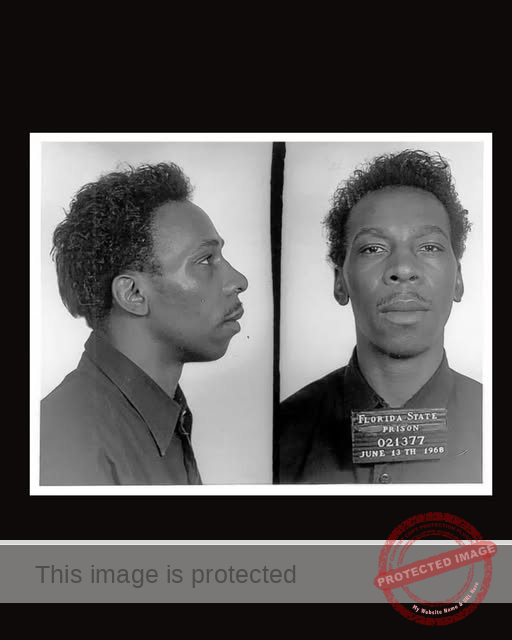

Richardson, a 31-year-old Black migrant worker, was illiterate and had no legal counsel. He was interrogated for 72 hours without breaks, enduring physical beatings and psychological deprivation. Under these conditions, he was coerced into signing a false confession, allegedly tied to a nonexistent insurance policy. The prosecution relied on fabricated testimony from jailhouse informants, and crucial evidence—such as Bessie Reece’s criminal history—was suppressed during the trial.

In 1967, an all-white jury convicted Richardson of first-degree murder, sentencing him to death. The case raised deep concerns about racial bias, especially given the systemic injustices faced by African Americans in the South during this period.

Legal Reforms and Richardson’s Exoneration

In 1972, a Supreme Court ruling commuted Richardson’s death sentence to life in prison. However, it was not until years later, after the work of civil rights lawyer Mark Lane, that the full extent of the prosecutorial misconduct came to light. In his 1970 book Arcadia, Lane exposed the false confessions and the intentional suppression of exonerating evidence.

In 1988, Florida Governor Bob Martinez appointed Janet Reno to review the case. Her investigation uncovered suppressed evidence, racial bias in the original trial, and the presence of perjured testimony. As a result, Richardson’s conviction was vacated on April 25, 1989. Charges were formally dropped on May 5, 1989, and Richardson was released from prison after serving 21 years for a crime he did not commit.

A Legacy of Advocacy

Despite the injustice he suffered, James Richardson’s resilience led him to become a strong advocate for wrongful conviction reforms. In 2014, he received $1.25 million in compensation for his wrongful imprisonment. His case brought attention to the flaws in the criminal justice system, particularly in rural Florida, where racial biases and systemic failures were prevalent. Richardson passed away in 2023, but his legacy lives on as a symbol of the fight for justice and the need for reform in wrongful conviction cases.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Strength and Justice

James Richardson’s story is one of unimaginable tragedy, but it also reflects the strength and determination of a man who refused to let an unjust system define his life. His case highlights the racial inequalities that persist in the criminal justice system and serves as a reminder of the importance of advocacy, legal reform, and the ongoing fight for justice for all.

Closing Line

This story may be updated with more information as it becomes available.